Then Big Jim Monday died. Quietly and with little notice for a man who touched so many lives. Including mine. In a very large and spiritual fashion.

Since cutting back on my blogs to focus on my book that was published recently, I haven't written many "They Call Me Flapjacks" pieces for awhile. Unless it involved the death of a newspaperman. In the last few months, I've written tear-drenched salutes to dead guys who happened to work with me during the half-century I've worked as a journalist.

Peter Cooper (who left journalism for guitars and museum display) died in December. Since he didn't spend his life in newspapers (though I hired him), perhaps I shouldn't refer to him as a newspaperman. He did a damn good job as my entertainment staff chief music writer, though. Better job, still, as my friend and biggest fan.

But Charlie Appleton sure was a newspaperman, throughout his life, and he died in February. He was kind of like a big brother to me, my shotgun passenger in the daily news wars. A kind and profoundly talented newspaperman, Mike McGehee died in January. He and I worked together and smoked cigarettes every predawn that we served as Nashville Banner editors. And I still miss Max Moss, my newspaper mentor, who died in 2021. He'll be with me every day, especially when I smile at the pica pole in my desk drawer.

Max Moss, left, and Jim Monday discuss front-page philosophy. This picture would have been taken sometime in the early 1980s. Max was managing editor, Jim copy desk chief, at The Leaf-Chronicle newspaper in Clarksville. I would guess this photo was taken by W.J. Souza, if he still was alive during that period.All were men I loved, and I still miss them and especially their voices, as I sit alone here in my basement office with the four clocks counting down life -- in Nashville, Bucharest, New York and Los Angeles time -- on one wall, a portrait of John Lennon on another and the wooden hand-carved angel that Tom T. Hall gave me, from him and his late-wife, Dixie, looking up at me. She wears Mardi Gras beads and a Beatles COVID mask I've given her.

"Dixie sure loved you," said Tom T, as he autographed it for both of them. I didn't realize it until months later that Tom T. was giving away stuff to people he thought might like it, who might collect memories, because he planned to end his life. Peter got a bunch of stuff from Tom T. He didn't live long enough to use most of it. I think guitar virtuoso Thomm Jutz and great harmonizer Eric Brace, two of Tom T's friends, do have stuff they have lived long enough to use.

A hand-carved wooden Chet Atkins nameplate -- he carved it and his widow gave it to me to remember him -- is on the shelf next to a copy of my book, Pilgrims, Pickers and Honky-Tonk Heroes. Chet's kindness to me fills up a chapter about him in this book that you should buy, and he reappears in other spots. There's a John Lennon "Give Peace A Chance" beer glass on the same shelf. Peter gave it to me at least 20 years ago after he emptied out the contents during December 8 Lennon death day celebration at a now deceased bar near Union Station.

I've spent the last couple months trying to help my book publisher sell copies of my book, filled with lively and often quite personal anecdotes from the mouths of those featured. And I've been fiddling about on a couple of potential follow-ups. Hadn't planned to do anything particular on this "Flapjacks" blog, though. I was sure something would come up I'd want to opine on or make fun of, but I had no topics that were urgent.

Until Jim Monday died....They say 87-year-old James Morris Monday had suffered a pair of falls and the second one on June 18 was fatal, injuring his God-loving brain. Peter pretty much died that same way, by the way, for those of you who keep asking.

I wasn't sure what I could write about Jim Monday, though. Because, even though he was old, I didn't expect him to die. No one ever called me an optimist, but I just figured he'd stick around long enough to sing at my funeral in 27 years. He had a helluva voice.

Sure, during our regular phone conversations -- I ALWAYS called him, as he was one of those who didn't realize phones worked in both directions -- he obviously was suffering the maladies of age. Dementia, hardening of the arteries, confusion, whatever. He still was a joy to have as a friend.

Old-guy confusion, perhaps, but he remembered me and our times together in the newsroom of the oldest newspaper in Tennessee. He remembered my wife, Suzanne, who also worked at that old newspaper for a couple of years.

I put in 14 years there, part of the time mainly because I loved the city of Clarksville, which The Leaf-Chronicle newspaper, founded in 1808, used to serve so well. Call 931-552-1808. No one answers in the newsroom. I called twice last week.

Corporate greed came much later than 1808. That newspaper -- where I worked 12 hour days, seven-day weeks as associate editor and with Jim as one of the stalwarts on the copy desk -- is now, like most newspapers published outside of New York and D.C. just a soulless receptacle and purveyor of press releases and shallow reporting. And the ones in the big cities are only alive because of costly life support.

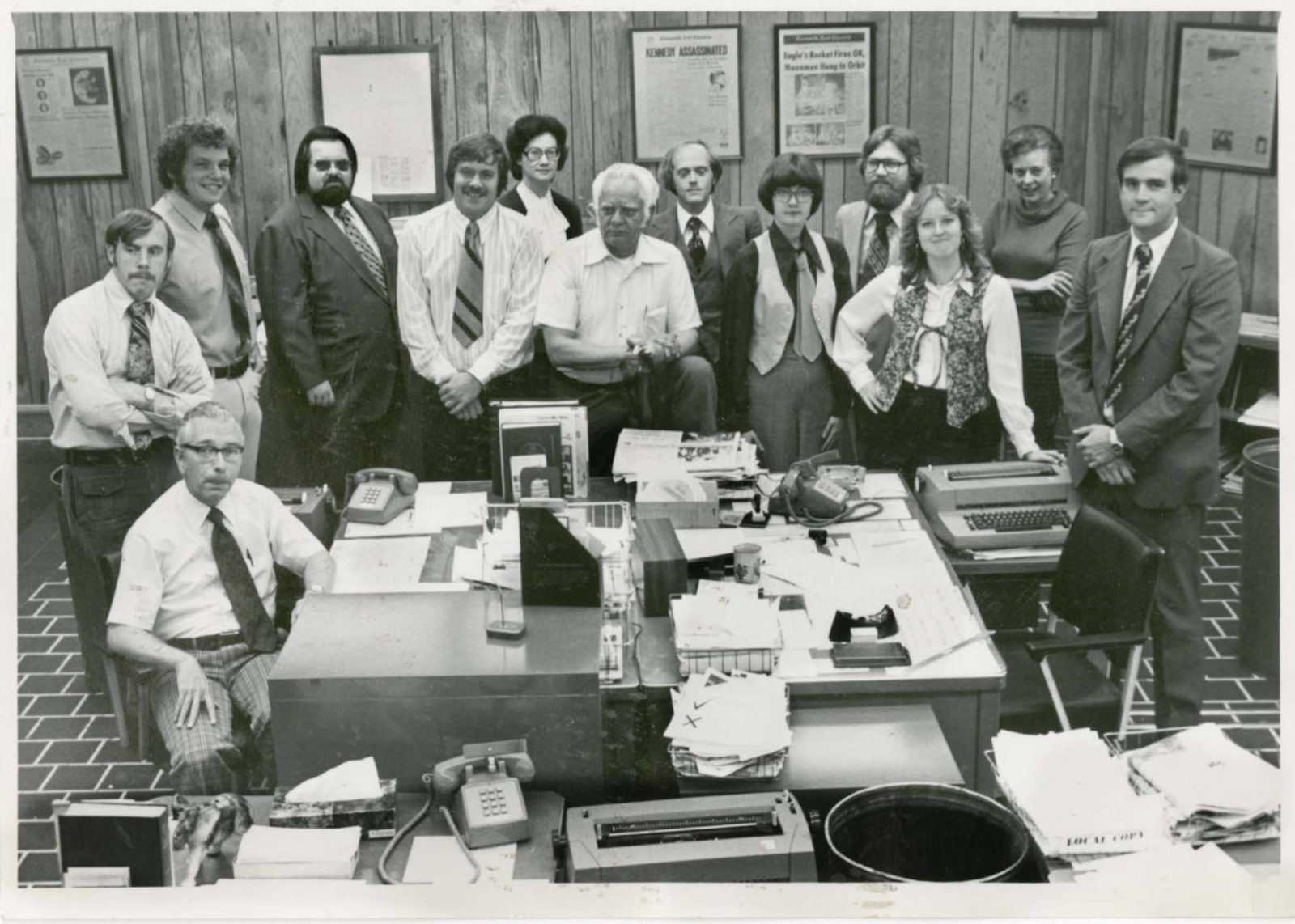

Jim Monday is third from left, between me and Larry Schmidt, in this 1970s Leaf-Chronicle newsroom photo. I'd name them all, but it would take up too much space (and I'm old). My mentor, Max Moss, is the guy sitting down. And photographer W.J. Souza, a WWII tank driver, is the old man in the middle.

I'm old and in the way, some say. Perhaps they are right. But 30-40-50 years ago, every Little League and society function and civic club speech was reported in The Leaf-Chronicle. All police reports were printed. Court agate was always there. (You don't know what agate is, and that's just sad to me. )The TV schedule was printed daily. The County Commission and the City Council were reported on, in detail, both in day-of previews and day-after coverage. With art (photos, you'd say). And everyone who died in Montgomery County received an obituary ... for free. If it meant killing a house ad or wire story, well so be it.

About 10 p.m. each night, as a last-gasp task, one of the staff, sometimes me, sometimes Jerry Manley -- my best friend, who himself has some health woes -- Jim, Suzanne, Larry Schmidt, Rob Dollar, Ricky Moore, Jim "Flash" Lindgren, whoever was available, would go downstairs for one last swing by the mail slot where the funeral directors would drop off the obit forms.

"Got George Smith's death notice," or something like that, the director would say in the one-way phone that was by that mail slot.

Sometimes, Mr. Foston, or another funeral director, would call one in from the embalming room. Right on deadline. One of us, an editor, a reporter, a sports writer, a copy desk honcho like Jim or Jerry, hell, even that asshole city editor (I won't name him here, but he knows, as do we all) would take the dictation.

Everyone who died before the newspaper's final plates were shot by Camera Room Foreman Ronnie Kendrick got in the newspaper the next morning.

Ronnie would be glad to reshoot a page if necessary to get the obits in. Last time I saw Ronnie, he was running a Waffle House, off I-65, not far from my house. That was his fate after a half-century at the newspaper. I'm sure it was him, though I didn't recognize it at the time. At least he appeared well-fed. I loved his mom, who would make me occasional caramel pies. I'd share them with the newsroom, much to Big Jim's delight.

Dropping everything to get the obits in may seem like a small thing, but it really was the most important service by local newspapers, or even big-city newspapers, back until the corporate snakes and money-sucking, bloodthirsty slugs took over and figured, "hell, we've been giving away this space for free. Why don't we charge people hundreds of dollars for their mom's obituaries? Most families will pay it. They're still in shock."

It's only in recent years that people have figured out that the internet, the tool that allowed the pigs to kill newspapers, was also the best tool for obits. Funeral homes put them on their sites for free. Or at least for a bit of overhead on the gluttonous casket costs. Only the frivolous pay to put their family obits in the newspaper.

All of which is kind of a collection of my loose thoughts while pondering that Jim Monday -- a caring, loving, peaceful big man -- died Sunday.

Not a word in The Leaf-Chronicle, where he spent his life, or its website by afternoon the day after. Heck, I may be wrong (I may be crazy), but following the internet trail, it appears that the first time Big Jim's final bow was noted in his newspaper for life was in the regular obits on Wednesday. One of the most-beloved people in that city had been dead three days by then. I am no internet wizard, and I certainly hope I'm mistaken.

I found out after a Facebook message from an old-timer, Gary Green, who I haven't seen in 40 years, said he had heard a rumor that Big Jim had died. But he wanted me to check it out for sure. He knew I'd want to find out if that was true.

First thing I did was call Jim's phone. No answer. "I hope you're OK. I love you, Jim," I said to the recording device. I was thinking "Jim is dead." I used a harsh expletive, one that doesn't belong in a story about Big Jim, even though he used to get red-faced and laugh when I'd pepper the newsroom air with it while exhaling clouds of smoke while waiting for Harold "The Stranger'' Lynch to get back from a meeting at City Hall. I have never been shy nor proper nor politically correct. Just principled and hard-working. And I always love my newspaper staff and colleagues more than just about anything.

Nothing on the Clarksville news websites about Jim right then, so I looked up the site of the most-likely funeral home. It had one line, just a name. "James Morris Monday" it said. Services were to be announced later, it noted. I figured it had to be my Jim Monday, but you never take that sort of thing for granted, and I called Neal-Tarpley and Etc. funeral home and asked. "Is the Jim Monday you have the old newspaperman? The Big guy who used to write the religion column?"

The nice lady told me the family had just finished making arrangements, but yes, indeed it was the old newspaperman. I am obsessive compulsive, so I asked two more times.

Of course, it was Big Jim. Damn it.

The Leaf-Chronicle, where he spent a half-century, had nothing on its website other than assorted filler and pictures from Bonnaroo, the music festival IN MANCHESTER. That's a long ways from local news in Clarksville, the type of news the son of Corbin, Kentucky, shepherded as a reporter, as a copy editor, as copy desk chief, as religion editor and columnist.

A competing site, ClarksvilleNow, got the obituary up later that day, with a huge portrait of Big Jim, and the full-blown obituary taken directly from the funeral home and reprinted. Chris Smith, editor at that site, had worked at The L-C, so he knew this death -- while likely not of import to the quarter-million or so folks who live in the area now -- mattered a lot to the 60 or 70 thousand who grew from childhood reading Mr. Monday's column. Perhaps even seeing his mammoth frame outside, in the city he loved.

"He was a great man," or some such, Chris said when I called to thank him for thinking about the old-timers, the ones who built Clarksville.

Big Jim spent 51 years or so editing and writing for the L-C, including post-retirement years continuing with his folksy "Open Line" religion-based, family-values based weekly column. Sometimes he'd write about his favorite vacation spot, Pigeon Forge. Or his visits around the country and the world to keep up with his daughter, who married a military man named Mike, I believe.

Jim stopped writing a few years ago. They had a big party to celebrate the half-century at his work. Then he quietly exited. Anyone who has "retired" from a newspaper in the last 16 years knows what that really means.

"I don't hear from anyone up there at The Chronicle, but there aren't many left these days," Jim would lament during our phone conversations from his home in Sango, the bustling suburb of Montgomery County where quickly rising homes fill the formerly pastoral community that used to be tobacco barns, ponies and Brown's Store, where old-timers gathered for dollar pool and canned Pabst most nights. Maybe open a can of Vienna (pronounced "Vi-en-nee") wieners and spit tobacco juice in the empty can.

Hank Jr. wrote a song, "Stoned at the Jukebox," after a stop at a roadhouse near where I lived for awhile. He was halfway between his Nashville and Paris homes/offices and he decided this dank Sango country bar was a good place to stop.

Getting a little off-topic, but, hell, a friend of mine is dead. Another newspaperman is dead. A newspaperman is someone who lives and breathes newspapers and as a result is poorly equipped to do anything else with their lives. Newspapermen don't willingly leave the lifestyle to become public relations guys or run a bank or become professors or water heater execs. They can't function properly on the "outside." Nothing wrong with any of those fields, but newspapermen simply cannot do that. Too cynical, too ethical beyond reason or health. No 9-5 and forget about it. There's always that headline you worry about or the cutline beneath the picture on the agate page. I suppose we should write a "newspaperperson'' sted "newspaperman" nowadays? ("Sted" is editor's bizarre lingo.)

And that is fine. My wife was a newspaperwoman/newspaperperson. My friend and former boss, Dee Boaz, was a newspaperwoman. Sara Foley, who I've lost track of, was a newspaperwoman (I put her in here just in case she sees her name). Jane Srygley was a newspaperwoman. Frances Meeker, too. Charlie Appleton and Joe Caldwell were newspapermen. Harold Lynch was almost unmatched. Richard Worden, too. Bob Battle. Joe Biddle. John Bibb. Mr. Russell .... C.B. Fletcher. The Old Lefthander. Vince Troia is still alive, but he can't stop trying to figuring out ways to be a newspaperman again. Ken Beck, same thing, although he keeps his hands in by writing. Same with Larry Woody.

Some newspapermen, like Rob Dollar, noted above, try other things, but can't be happy as anything but a newspaperman. Jerry Manley, too. I used to drink with those two newspapermen after the presses rolled. "You know we're society's misfits. All newspapermen are," I'd say. They'd laugh. But nod. "Nothing else will make us happy."

Publishers can even be newspaper people. Luther Thigpen was one. So was John Seigenthaler. Irby Simpkins and John Jay Hooker, well, not so much. You get the picture.

Gender regardless, they all were of the impression that what they did daily, from obits to cutlines to making sure the right crossword puzzle answers were in the paper, mattered.

We didn't find out otherwise, until Korporate America chimed in that it really didn't matter, nor did we. What matters are dollars.

I first met Big Jim on September 12, 1974. That was the day I began my first newspaper job as a high school sports writer.

Sports Editor Gene Washer had hired me a week earlier, but I hadn't had a chance to meet the staff. They all were chain-smoking, pounding on typewriters, tearing copy off the UPI and AP machines, sending page layouts and copy to the second floor typesetters via pneumatic tube. Pica poles cut like switchblades through the thick, blue smoke.

It was a glorious, near-cinematic sight. Editor didn't like the story? It was violently impaled on a spike for consultation with the reporter later. Everyone who edited copy had a spike, a chunk of square lead with an eighth-of-an-inch-thick, 6-inches high piece of steel with a deadly point on the top. Eventually, OSHA came through and demanded the spikes be emasculated by bending the tip down, the formerly fierce jutting metal turned into a limp "U." I still have my spike, with the extra pica poles, in a box in the garage. Got a scale wheel, too.

The day I finally met Big Jim and the rest of the staff was short on introductions. My direct supervisor, Max Moss, handed me some local football stats to type up. Jim sat a few feet from me at the head of the copy desk. He was a mammoth man, who slimmed down considerably as he aged. He had a flattop haircut. A typical good old boy appearance. With the sweet soft voice colored by welcoming warmth in his greeting. That assured me I truly was in the right place.

I bummed a smoke from Max and went to work. I smoked in college, but I had quit. It took one hour in the blue-smoke cloud that hovered over the L-C newsroom to break me of that no-smoking habit. Hell, if you gotta breathe the stuff, might as well enjoy it. I finally quit smoking a quarter-century later, after firing them up with Eddie Jones, McGehee and other dead guys during my second newspaper job at the Nashville Banner.

I quit smoking four years into my work as entertainment editor at The Tennessean, something Bibb lamented, because he bummed at least one a day from me. A small price for being able to share time with one of the most legendary of sports editors.

Big Jim quit long before, as far as I know. He eventually let his beard and hair grow out, giving him a sort of extra-large Jerry Garcia appearance.

And, like I said, he began losing weight.

But he really didn't change. Big Jim was a local journalist, in the best sense. He encouraged his copy desk staff and led by example. He later was switched to No. 2, behind Jerry Manley, when we turned to an ayem product.

Jim oversaw the desk during the daytimes, Jerry at night when deadlines loomed.

Jim also was worshiped in Clarksville for his Sunday column.

During our phone conversations in recent years, I'd encourage him to put together a collection of those columns for a book. "Old Clarksville will love it," I'd say.

I don't think he ever did.

I have done my best to keep up with Big Jim over the years, 5-1/2 years ago even attending his late-in-life wedding (his first wife died long ago). We spoke frequently, but he was forgetful, even in the same conversation. Still I loved the Big Man.

"We sure used to put out one helluva local newspaper," I'd say.

"It's not like the old days now," he'd say. "But we really did a good job."

I should mention he also was a gospel singer of some renown. I have a CD of him singing old-time religious numbers and some he wrote. Jim also was my key into the gospel and pork barbecue worlds when I was in Clarksville. One day, The Pettus Family Singers -- cousins of local running sensation Wilma Rudolph -- came into the office to sing a few spirituals for Jim.

I introduced myself, and within days I was spending my free evenings at a barbecue stand across the river from the city, where Ole Steve Pettus taught me how to smoke whole hog and shoulders. Steve had been one of the singers, of course. His brother, Euless, often helped with the smoking. And I ended up being a fairly white face at the family's annual picnic. Wilma was there, too. And wherever they were, they sang harmonies of God and heaven.

That's all another story.

Heaven is a concept, of course, debated by many people. Regardless of that debate, Big Jim is up there now, his lilting tenor making Gabriel smile.

A few other things. Because of his desire to live a full life -- and he did -- he probably lost 150 pounds since I first met him. There was some of that weird "he looks so good" stuff from those who stood by the open casket Saturday. I'm glad some find comfort in that almost-lifelike appearance.

He loved pie and ice cream. And cornbread. And barbecue. And Red's Bakery's double-stuffed potatoes. And life.

He hated it when Red's Bakery closed, by the way. We all did.

He loved the family that surrounded him when he died and who gathered Saturday, June 24, in the funeral parlor.

I was fortunate in that after Suzanne and I made our seat selection we were joined by Dee and by Carolyn Lynch, Harold's widow, and their son, Chris. "This is an L-C row," said Dee. I only saw one other Chronicle person there. Suzanne reminded me that probably most of the people I worked with 36 years ago -- when I left L-C -- are dead. She was only half-joking.

Jim Monday absolutely hated what had happened to the newspaper where he spent his adult life.

"I'm just glad we came along when we did," he'd say, and I'd agree. "Glad we're not young. They'll never know what a great place a newspaper was. Being a newspaperman."

Even though he was 87 and had obvious health difficulties, I always hung up figuring there'd be another conversation.

I guess that will have to wait, I hope a few years. I may be a cynic, hardly the man of Christ like my friend. He had no doubts there was a heaven. That we'd all see each other again.

I'm hoping Jim Monday was right about that.