“You are my best friend,” I said, fighting to keep my voice from shattering as my writing partner looked at me, a moment before his heart stopped.

It was about 12:30 a.m. on November 18, 2023 … a half-hour into my 72nd birthday, one that will never be remembered for candles and cake but rather always carry heartache and hints of hurt … until my own journey into the blackness into which my best friend would embark.

“You’ve always been a good boy,” I said, stroking Champ’s head. “Beautiful boy. You’ve been my best friend for a long time now.”

Even though

blindness had accompanied his downward spiral in recent months, accelerating as

autumn chill had settled in outside the French door where he would let slanting

sun warm his frail body, the light disappeared from his eyes quickly as his

heart stopped on what will forever be my most somber birthday.

My wife -- who never minded that I referred to my office

assistant as “my best friend” every night before he settled down on my chest …

or simply when he vaulted into my lap here in my office, as I began my daily

quest for words to string together -- stroked his back and told him “We love

you, Champ. You’re a good boy.’’ If she was trying to hold it together for my

sake, she failed. “You’re such a good boy, Champ.”

Champ had always sought out Suzanne when he needed

comforting, whether in a thunderstorm, when neighborhood scalawags celebrated

July 4 or the New Year with bottle rockets or when workmen cursed and slung

hammers against nails during various renovation projects. Champ had lived through many of those in our

home, a 1956-model brick rancher in Nashville’s Crieve Hall neighborhood. Other than his annual physical or the

occasional visit to the heart specialist to monitor an eventually mortal

defect, he’d never been anywhere else.

In the hours before his death, he laid, gasping, on Suzanne’s

outstretched legs and lap. He would try to purr. But then he’d cry, a soft, cat

whimper. It was time, we knew. All three of us. We wanted that journey to begin

and end at home. But that bad heart, his long-ago forecast fatal flaw,

struggled to keep him going, faintly, in fits and stops, as fluids filled his

lungs. He was struggling, even as he spread his love.

Champ had been with us almost 12 years, after I picked him

out of a Nashville Humane Society cage.

Everyone else in the cat room that winter’s day was playing

with and adopting kittens. It was the

full-grown fellow, at least 2 years old, that I pulled from his cage. He was happy about that. Me, too. I had

called the Humane Society to see if any of their population already had been

declawed. I didn’t want to do that to a cat, but if the deed had been done, I

wanted him in my house rather than with someone else, who might let him wander,

defenseless, as so many cats do. Too many coyotes and vermin around the woods

behind my home.

“We’ve got one older cat here who’s been declawed,” I was

told. “His name’s Mike.”

I asked for them to put a “hold” sign on his cage while we

trekked the 20 minutes from what was to become Champ’s lifelong domain.

On that long-ago December 29, my daughter Emily, and my son,

Joe, sat with Suzanne in the glass room where you “try out” cats. They’d all

been looking at kittens, while they waited for me. Their eyes sparkled when I

entered the room with the tabby in my arms’ crotches.

“This is the one I was telling you about. His name’s Mike,

but that’s no name for a cat,” I said, handing the handsome eight-pounder to

Suzanne.

The beautiful cat began campaigning for adoption, wandering

around the little room, spreading purrs and rubbing against legs. He didn’t

know the decision had been made as soon as I made that phone call, less than a

half-hour before I lifted him from the cage and he purred, contentedly.

It was the birthday of my late mother, a cat-and-dog lover

named Dorothy Champ Ghianni. Suzanne suggested we call him “Champ.”

It fit. I didn’t know at the time that he would become my

office assistant as I wrote my yarns, mostly melancholy ones. My name’s Timothy

Champ Ghianni. Jocko, or maybe it was Nardholm or Carpy… maybe even Uncle Moose

… dubbed me “Champo” in college. Those from Hanson House who survive continue

to call me Champo. It’s been a life full

of nicknames. There remain a few who call me “Flapjacks,” a name I earned

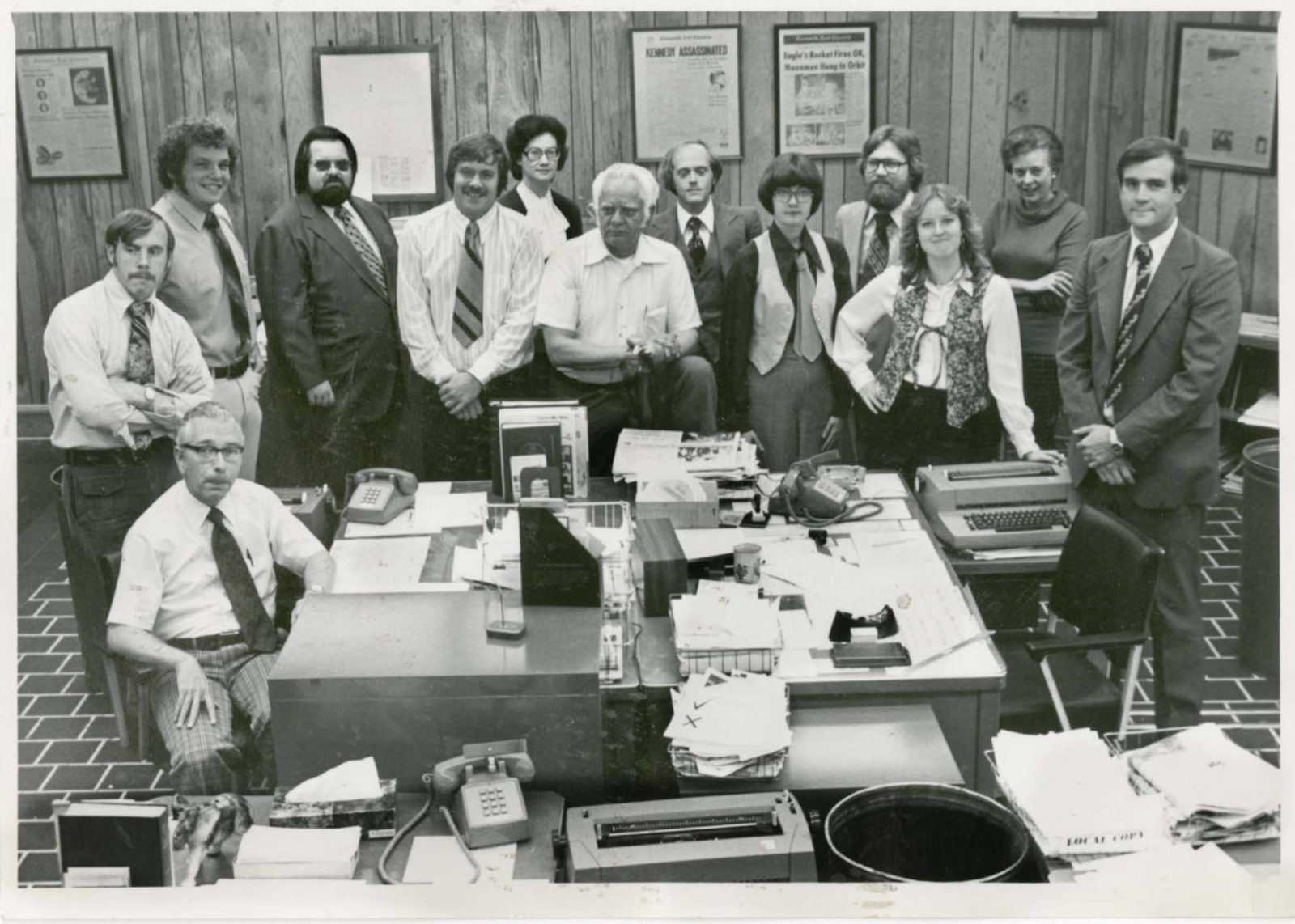

during caffeine and nicotine-fueled newspaper deadlines, back in my favorite

professional days. That’s another story. There’s a book about those days if you

are interested.

When we got the former Mike to our house almost 12 years

ago, Champ immediately strutted, calmly through his home, the place where he’d

reign. He found the litterbox in the utility room and his food and water dishes

at the kitchen’s edge.

He was sweet and happy, immediately. Suzanne took him to the vet in the next day

or so, and the doc was concerned. He sent Suzanne and Champ to the specialist

who detected the major flaw in the cat’s heart. “He’ll only live six more

years, at the most. If he’s lucky.”

We were the lucky ones, as he spread love and devotion in

our house for 12 more years.

Quickly, Champ learned how to chase the melancholy from my

soul – admittedly it sometimes ends up in my dispatches as I continue a life of

chasing away the black dogs of depression – just by his presence.

My newspaper life ended in 2007. That’s another story, and it can also be

found in that book I referenced earlier. It’s a story about personal ethics versus

corporate tyranny. And it doesn’t have a happy ending. The scars exist still,

and Champ, when he joined us, helped me cope with that still, long-lingering pain.

That’s all beside the point of this little tale, other than

to note that on December 29, 2011, when Champ first moved into what became his

house, the beautiful cat learned that a great place to spend the days was in my

lap as I sat before my computer. Soothing any sourness in my soul as I composed

news and feature pieces, class lessons, blogs and authored five books.

His calming attitude worked well, as I typed my way through

a jumbled career that included freelance work (sometimes for free if I thought

it might help my friends in music or the arts…. My heart and personal loyalty

long has outpaced any push for riches, which is fortunate.)

I also wrote for a

major news service for a decade, a job I lost in the heart of COVID and when

Reuters began trimming its part-time freelance staffers. An every-other-week, slice-of-life-and-news,

people-focused column I had written for a decade for Nashville Ledger similarly

died of COVID cutbacks. Champ also sat on my lap as I worked hard to prepare

writing and stylebook lessons and quizzes for my journalism labs at a local

university. When all those long-running jobs

died at about the same time, ending consistent income, Champ sat in my lap and

purred. Sudden loss of even minimal income wasn’t important to him. Or to me,

thanks to Champ.

Life cannot be bad when you’ve got a cat who loves you

unconditionally in your lap and a great family around you.

Champ was with me from about 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. daily,

seven-days-a-week while I wrote my latest book, Pilgrims, Pickers and

Honky-Tonk Heroes. He was there when I called friends like Duane

Eddy, Kris Kristofferson or my dear pal Bobby Bare to talk about what I was

writing.

He was with me when my best human Nashville friend, Peter

Cooper, who was editing the book for me and who wrote the foreword, spoke to me

about what I’d written during that year of typing and remembering. “Change

nothing,” he’d say as he concluded each chapter, suggesting only minor grammatical

or punctuation changes. “It’s beautiful. It’s written only as you could write

it, Timmay.” (That was another nickname I earned, one used only by Peter. I

also had been dubbed “The Dirt Man” or simply “Dirt” by my friend, my long-ago

Tennessean entertainment staff gossip columnist Brad Schmitt, who continues at

the paper, where he provides good-news and tasty filet/buttered biscuits tales….

Back in high school a bloodthirsty football coach dubbed me “Brahma Bull,” but

that tale is long, painful and is in another of my books. My head still hurts,

though.)

In 2019, when my Dad succumbed to his World War II-age and

corresponding maladies, I would spend quiet time, mourning, with Champ on my

lap. Dad used to watch Champ when we went on our seldom vacations, and I think

Champ likely knew his “Grandpa” was gone.

Champ climbed in my lap each day last December when I’d get

back from the hospital where Peter Cooper lay dying after damaging his brain in

a hard fall a year ago Friday, December 1. He died five days later, and I miss

him and our almost-daily phone conversations.

My office assistant’s soft purring helped me survive those

blackest days. I cried, while Champ

nudged his face against my own, calming if not fully chasing away the tears of

heartbreak over a beloved friend’s too-young exit. Champ’s purr and his gentle

head nudges were his way of saying “I love you. Everything’s OK.”

I wish Champ’d been

able to calm me the other night, early on my 72nd birthday, as I

wiped the tears and petted his still body.

“He’s still beautiful,” Suzanne said, as she battled her own

heartache. Her lap of solace for Champ would forever be empty now.

A major reason for our own love story, dating back into the

1980s, was Suzanne’s love of animals matched my own. To many, pets are for

entertainment, accompanists to neighborhood struts. And that’s fine. As long as

they are loved.

To others of us, they really are family members. There is

incredible weight in this attitude, as we know they will only be with us an

abbreviated amount of time.

Of course, Suzanne really is my best-best friend, she is a

former lifelong journalist who loves animals. Fact is, our only real difference

is that she turns to Matthew, Mark, Luke and John; while I find my solace in John,

Paul, George and Ringo.

My mother -- or maybe it was James Thurber, James Herriot or

cat-lovers Ernest Hemingway or John Lennon -- said long ago that the greatest

gift pets give us is they prepare us for death. If we can say goodbye and not

totally break when a pet dies, then perhaps we’ll be able to handle the deaths

of parents, grandparents, best friends, work colleagues and Beatles.

True enough. But then, what prepares us for the death of our

pets? One who is a best friend? I know the writing rules call for pets to be

“its” and “thats” and only humans dubbed “whos,” but that’s heartless and

complete bull shit.

Every year, near but never on my birthday, I write a column

or a blog. I write it for me, soothing or cleansing my brain... It’s sort of a

State of the Union, or a State of Old Timothy Address, a rundown of my

thoughts. Generally melancholy, as I am, I run through what I’m thinking, what

I’ve accomplished and how I’ve failed in the previous year … and then reflect

back on the now 72 years since I was born in Saint Joseph Hospital, a dandy Catholic

joint, in Pontiac, Michigan.

I often don’t publish it. It’s just for me, a way of busting

through the cobwebs of death, disappointment and defeat that have been spun

during the previous year/years. Oh, I do celebrate the triumphs, too, like the

success of getting a major book publisher to take on my recent book about the Pilgrims,

Pickers and Honky-Tonk Heroes I had befriended.

I never published last year’s for example. It began with a

litany of bad things that had accompanied my year and the good things, like my grandson

(I now have a granddaughter, as well), my children’s successes and my spiritual

bond with Peter. Before I could post it, Peter fell, hit his head and died. I

rewrote that year-in-the-rearview meanderings to reflect that loss – but I

never published that 2022 State of Timothy Address. Too damn sad. I did write

and post a separate piece about Peter, as I thought it might help the many

others who mourned him. And writing

always has been my own salvation.

Last I looked, the 2022 State of Timothy Address was about

15,000 words, as long as a novella. Perhaps if I ever do a collected works,

weird scenes inside the goldmine that is Champo/Flapjacks/Timmay/the Dirt Man

and Brahma Bull, I’ll include it. I’ll give you a hint: Nobody wins.

I read through that unpublished 71st birthday declaration

again as I was thinking about Champ’s death on my 72nd birthday.

There are several mentions in that one of that wonderful cat and how he helped

me cope.

For example, near the end, I say:

Now, I am fortunate. I have a nice, little house in a

prime Nashville neighborhood. I have been married 30-plus years to my best

friend. And I have two kids and a grandson.

And a cat, who helps me write this stuff.

Again, that was just over a year ago, on my 71st

birthday.

That cat isn’t around to help me on this one. He died and

there was no cake. Just tears.

One thing Champ had to endure over the years was my love of

music. For years now, I’ve been pedaling my recumbent stationary bike daily for

miles to nowhere in my basement. That bike sits right next to my office door.

Sometime, usually in the mid-afternoon, I put on my favorite

music – The Beatles, Rolling Stones, Tom Petty, The Traveling Wilburys, Bare,

Kristofferson, Dylan, Cooper, Brace, Jutz, Byrd and death-era Cash.

At least 60 percent of the time, it’s The Beatles, as a

group or separately.

And I begin the daily toil designed to keep my own heart

healthy. I pump ‘til I sweat, climb off to arrive where I began.

Champ, who always claimed my office chair as his own as soon

as I ducked out from beneath him, would just sit in the chair – he frequently

spent his nights there in recent weeks, I guess because it was comfortable,

smelled like me and he could find it in the darkness that had become his

worldview.

He’d watch through the office door as I pedaled. Or at least

look toward the sound.

Last week, in the days toward his decline, Champ heard an

awful lot of Beatles. For some reason, I’ve been exploring the outtakes from

John Lennon’s Imagine album package of a few years back, seeking answers

or just smiles. Champ always seemed to like John’s voice. I’m sure he was particularly fond of John’s

description of life’s peasants in “Working Class Hero.”

If I was playing The Stones,

for example, he might get down and wander upstairs and jump in Suzanne’s lap to

avoid the Crossfire Hurricane. Jumpin’

Jack Flash may be a gas, gas, gas; but it’s difficult on feline ears.

Lennon, whose voice soothes me as well as provides heartache

because of the fact he died more than 40 years ago when he could still be

making music, seemed to be a favorite of Champ’s.

Course I don’t know that. I just know Champ sat quietly in

my office chair as John sang by himself or with his Scouse cronies on my old stereo.

I’m not sure what was the last song my beloved office

assistant heard. It could have been “Imagine,” “Crippled Inside” or a long

piano solo from those Imagine outtakes, that to me are better than the

finished album.

Thinking back to that day, as I write this, though, I’ll

wager it likely was a “new” song – The Beatles’ hit record “Now and Then” – that

I’ve been playing several times a day that Champ last heard.

It’s John Lennon’s voice from the grave, an old cassette

demo that was brought back to life by Paul McCartney, Ringo and Giles Martin. A dead George Harrison plays guitar and

harmonizes.

Some say, and I am among them, that the cassette left behind

by John was a sort of love letter to his life’s best friend, his truest

companion on the road through life, Paul. The two boys from middle-class

Liverpool changed the world, with the help of a couple other Scousers. Some are

dead and some are living.

Truly, the last music my beloved Champ likely heard included

John’s purified voice singing: “Now and then, I miss you.”

It’s very true that Champ helped me write stuff all of these

years. Often, I wrote through too many

disappointments, deaths and betrayals. Champ calmed me with his purr or head

nudge, triggering emotional rescue. Then, and I’m thankful, my words would

smile.

Accomplishments, like having a book published that was

praised by Kris, Peter, Bare and more, also were put into perspective by his

steady support and encouragement. Keith Richards got a copy of the book in

trade for loaning me a couple of photos published inside, and I hope, even

though it’s not only rock ‘n’ roll, that he liked it.

Sitting here in Champ’s office chair, thinking of the huge

hole in my heart and the shock-induced nausea and diarrhea as his death exacted

a physical toll on Champ’s favorite writer and best friend, he’s still here

with me in spirit.

My lap is empty, and it’s colder down in the basement

without Champ.

I keep looking at the chair when I come down to the office.

Champ: Now and then, I want you to be there for me.

Only in memories and warmth in my soul.